A Brief History of the NSF & Why We Need It

My thoughts on why the National Science Foundation matters, as a GRFP fellow

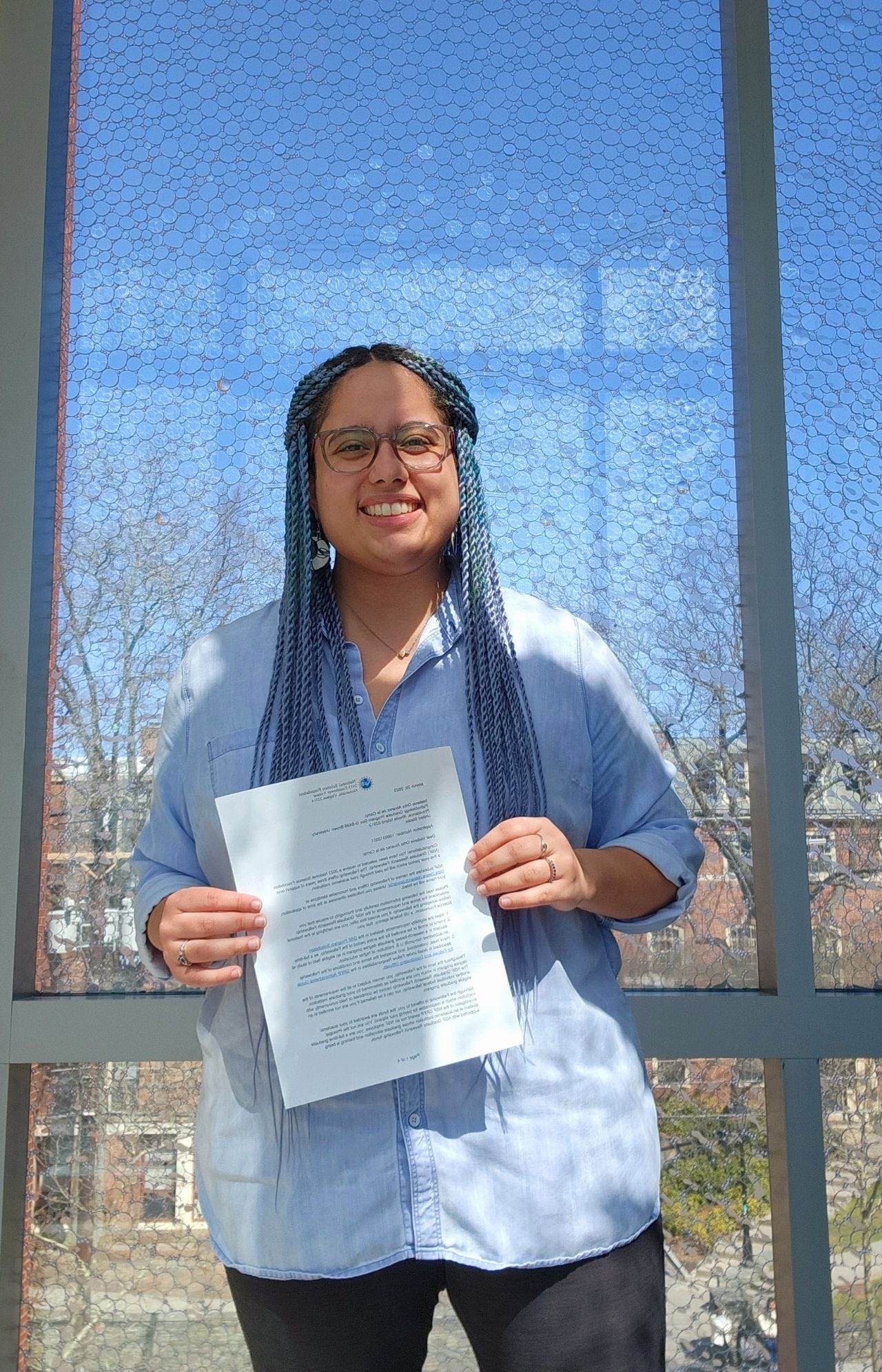

Here’s a picture of me from the day I found out I was awarded the NSF GRFP. This is a fellowship that funds 3 years of a PhD degree. Thanks to that award, I’ve been doing research about finding new ways to treat anxiety in children and adults. Yet, this fellowship is one of the many opportunities at risk due to budget cuts.

Let’s rewind to the 1940s. World War II had just ended, and the U.S. was reckoning with what science had made possible (atomic bombs, radar, antibiotics) and what it could do next. The government had mobilized researchers to help win the war, and it worked. But when the war was over, a new question emerged: how do we keep that momentum going in peacetime? Who funds science when there's no war to fight?

Then came Vannevar Bush. Bush was an engineer and science advisor who had led the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development during the war. In 1945, he wrote a report called Science, The Endless Frontier. This report made the case that federally funded science, especially basic research, was essential for the country’s health, security, and economy. He argued that research should be driven by scientists, not the military or politics, and that government investment in science was an investment in the future.

That report laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the National Science Foundation (NSF). It wasn’t a quick or smooth process. Congress debated the structure and scope for several years. But finally, in 1950, President Truman signed the NSF into existence.

At its core, the NSF was created to support basic scientific research across disciplines, independent of immediate commercial or military interests. It wasn’t just about producing new technology; it was about building knowledge, training the next generation of scientists, and making sure the U.S. stayed at the cutting edge of discovery. And it was meant to increase science communication.

From the beginning, the NSF was meant to bridge the gap between science and society. Bush believed that the public should understand and value science, not just the breakthroughs, but the process. Over time, this vision evolved into something more structured. In the 1980s and 90s, the NSF began funding more formal efforts in science education and outreach. Programs like Broader Impacts were introduced, requiring grant applicants to explain how their research would benefit the public, whether through education, outreach, or real-world application.

This shift wasn’t just a bureaucratic checkbox. It marked a turning point in how scientists were expected to engage with the world outside their labs. Suddenly, writing a paper wasn’t enough. Researchers were being asked to give talks, mentor students, create websites, partner with educators, and learn how to explain their work in plain language.

And while some people grumbled about it, others saw the opportunity. The rise of science communication as a professional field. Science writers, museum educators, YouTubers, TikTokers, even Substack bloggers (👋) can be traced back in part to this growing emphasis on public engagement.

Today, NSF funding supports science centers, citizen science projects, storytelling workshops, media fellowships, and critical basic research that shapes everything from climate policy to AI regulation. It’s not just about pushing the frontier of science forward, it’s about pulling the public in, too.

Which is why the current threat to NSF’s funding is so alarming. In 2025, the U.S. House of Representatives proposed slashing the NSF’s budget by over $1 billion—roughly 30% of its current funding. This would mean fewer grants, fewer jobs, fewer opportunities for early-career scientists, and less support for public-facing science communication. This is a direct hit to the future of American research, innovation, and education.

Science doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It lives in classrooms, on social media, in policy decisions, and in the lives of people it touches. I wouldn’t be where I am today without the support of several fellowships, including the NSF GRFP. If we don’t protect the infrastructure that supports that work, we risk losing more than just experiments, we lose progress.

So if you care about the future of science, the stories we tell and the discoveries we make: now’s the time to act. Call your representatives. Write an email. Tell them why NSF funding matters. Because the story of science in the U.S. isn’t finished and we all have a part to play in what happens next.

Resources:

Silenced Science Stories Initiative

Thanks for reading.

I’m glad you’re here :)

Mel

If you liked this post and want to further support me, consider subscribing:

Or, buy me a coffee :)